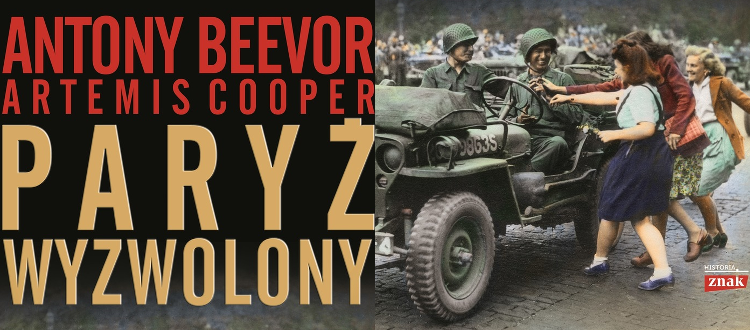

Paris After the Liberation…, liberating from prejudice and ignorance, was described by two British researchers – Antony Beevor, a well-known historian of WWII and Artemid Cooper, the author of the colorful biography of Patrick Leigh Fermor. Among other works about the French capital in the first decade after the war, Beevor and Cooper’s book distinguishes itself as being a great drama, a crime, and a guide in one. Although it describes Paris of the end of the Second World War, it may or even should be, as the Polish publisher advised, a compulsory reading for those going to Paris for the first time.

Thanks to the clear and original interpretations of the authors we can learn not only about the cool architecture of the city, but also about its heart – the people who breathed life into it. So Paris After the Liberation… is the story of people who at the end of the war found themselves in a unique place – those who survived the Hell of World War II and those who were under the impresion that it just past them. In the shady cafeteria on the left bank Sartre, Camus and Beauvoir sit side by side; at the next table, despite the early hours, some young couple is rocking to a jazz melody. The colorful socks of a zazou (a prototype of the beatnicks), waiting for someone at the entrance to the cafe, catch their gaze. Opening Paris After the Liberation…, we also encounter the debunked figure of general de Gaulle and politicians attempting to win something for themselves first, and then for France (heroes such as Rene from Allo! Allo! do not appear, and only representatives of the Communist Resistance Movement are proudly presenting their breasts for nexts medals). Many protagonists want to forget the past war – because they do not feel like the winners or the memories of atrocities encumber daily existence. The post-war city, even if bathed in the most beautiful sunshine, smells and music, means poverty and dread, anxiety for tomorrow, and at the same time a maniacal, restless joy „that bad times have already passed”. Oran from Camus’ The Plague might have looked like that. Melancholia and feverish excitement, almost tramping on each other’s heels, are strolling along the streets. Beetwen them appear Americans, confused and not understanding too much of all that ferver. The sounds of an accordion cannot drown out the sense of shame. Dancing zazous cannot chill out the atmosphere; students in black turtlenecks absorbing books, also did not possess such skills. Only the consciousness of ordinary people, who going for the daily shopping pass the Louvre, can divide time into the war and the time who has just arrived.

Historians will struggle for years over what happened in France during the war, and the farther from its end, the more polarized their assessment will be. Paris After the Liberation… is a must read for those who want to better understand what the war took from, and what it brought to France.

Joanna Roś